Ardcanaght, County Kerry, Ireland 1816

Ardcanaght, County Kerry, Ireland 1816

The night was clear, and for once the wind was still. Dew

blanketed the pasture. Breath hung in the moonlight. Thomas Griffin carried the

bottle full of Easter water, blessed by Father O’Sullivan only three weeks

before on Palm Sunday, out of the one-roomed thatched cottage he shared with

his wife Mary. He picked up a palm branch and pulled the wooden door closed

behind him.

It was the night of April 30 1816 – May Eve. The winter was

over at last and the days grew warmer and longer. Thomas had important business

to attend to.

“Plenty of dew for the mornin’”, Thomas thought to himself

as he made his way to the furthest corner of his field. In the morning he and

Mary will wash their faces in the morning dew for good health for the new year.

“As good as holy water.” Mary told him.[i]

He poured a few drops of the holy water on the branch and

caressed the furthest fence post.[ii]

Job done he did the same to each other corner post. The cow stared blankly

ahead in the dark as Thomas sprinkled and caressed its back. He had already

done the same to the pigs and the dog which lived inside with them all. For

good measure he draped the cow’s horns with a marigold and buttercup.[iii]

Mary had earlier spread marigolds, primroses and buttercups

– any yellow flowers – around the outside of the house to keep the cailleachs

away. Cailleachs were old hags who would steal milk or butter on the morning of

May Day.[iv]

Even worse were the fairies. The Ardcanaght flatlands were flanked

on two sides by mountains – MacGillycuddy’s Reeks to the south and Slieve Mish

to the north. On May Eve the distance between the real world and the Otherworld

is the thinnest, and fairies loved to hold their parties in the hilltops,

plotting to swoop down and steal anything they can lay their hands on, like

milk or cream.[v]

Thomas stopped to stare at the dark outline of Slieve Mish, and was sure he

could hear music drifting through the still air. Time to get inside.

Father O’Sullivan was fine with his flock sprinkling the

holy water about – it had been blessed, after all. But he drew the line at

flowers and fairies and cailleachs – “Pagan nonsense. When will these people

ever leave all that behind?” he sighed.

Mary was due to give birth any day and sat uncomfortably in

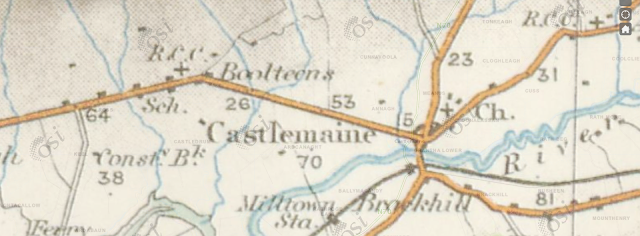

front of the hearth. Frances Brien, the local handywoman from Castlemaine, had

been around earlier in the day to check that all was well. Thomas was banned

from the house while this was going on and spoke to Frances briefly when she

left.

“She’s fine,” said Frances. “Could be tomorrow, or not,” she

added not-so helpfully before making her way off down the muddy track. “Beware

the fairy changelings tonight!”

Frances Brien was a highly respected local handywoman, not

least because she often travelled long distances, often at night, and alone, to

assist women in labour. Sometimes men from more remote places, like in the wild

and windy valleys of Slieve Mish, would walk many miles to meet her so that she

did not get lost.[vi]

Her only experience was that of delivering her own children – all five of them

– but Thomas knew that Mary respected her advice and wisdom. So that was that.

Ardcanaght was not far from Castlemaine, so Frances was not too put out this

time.

“Do you think it will be tonight?” Thomas asked as they

settled in to sleep.

“If it’s God’s will”, Mary replied wearily. “But I’m ready.”

Thomas noticed the butter in a cup beside the bed. Some

people said that giving birth on May Eve was likely to tempt the fairies to

come down and abduct the mother on May Day morning.[vii]

Butter in the mouth kept them away. “Frances Brien told me to keep it there,”

Mary said as she closed her eyes.

It was a biting cold night. Amidst the stillness the cailleachs

wandered, as cailleachs did, searching for human fallibility. The fairies

partied and danced in the distant hills. Mary slept fitfully, shifting position

as the baby kicked and elbowed. Thomas lay half awake, listening for movement,

inside and out. But by first light Father O’Sullivan’s holy water had kept the

netherworld away. Still, the most dangerous time was ahead.

“It’s time,” Mary said. “Go fetch Mrs Brien!”

Thomas knew that he could not leave Mary alone, so he

quickly ran to Ellen Mahony’s place a few hundred metres away. He knocked on

the door in the freezing dawn light. Ellen dutifully Jesus, Mary and Josephed her

way to assist Mary.

Ellen thus dispatched, Thomas ran as fast as he could to

Frances Brien’s house in Castlemaine. They both returned to Mary within the

hour. Ellen had boiled some water and had reached the third decade of the

Rosary when Frances and Thomas arrived.

Thomas waited outside. Inside the sounds of prayin’ and

groanin’ were overlaid with Mrs Brien giving firm instructions, then more

groanin’. Ellen was now up to the fifth decade of the Rosary, and smoothly

Glory Be’d into a new Rosary once the first was finished.

Thomas Garvey approached. He had a sailor’s gait, which was

odd because he had never been within a bull’s roar of a ship. Perhaps it was

from straddling rows of potatoes and corn all day long. Thomas was built like

one of those sturdy corner posts Edward had sprinkled with holy water and he seemed

to not have a neck. When he spoke he seemed to stare over your shoulder. Together

the two men moved away from the women’s business and sat under an apple tree near

the road.

Thomas Garvey was a great friend, but tact was not his

strong point.

“Remember that O’Connell woman, Elizabeth, I think – married

Michael O’Byrne?”

“I do”.

“Stolen by fairies she was, even while havin’ the baby. Changeling.

She was dead. They was all wailin’ an’ keenin’. Michael came in, saw his Lizzie

lyin’ there, walked straight outside he did, grabbed his pitchfork, came back

in, stood over his poor dead wife, raised the pitchfork – an’ the fairies took

off. Lizzie came back she did. From the dead! And the baby came along all fine.

Of course, Father O’Sullivan wouldn’t hear of it. Nonsense, he said. But it’s

true!”[viii]

Thomas knew his friend Thomas Garvey was just trying to do

the right thing by keeping him company, but this wasn’t helping.

“She’ll be fine – she’s a strong woman, my Mary. She’ll be

fine.”

“Cow need milkin’?” Thomas Garvey said.

“Yeah. Maybe you could..?”

“Sure.” Thomas Garvey bolted over to the pail, and off to

the job he had allotted himself.

Thomas was left alone with his thoughts. He didn’t have many.

He was tired from lack of sleep, and just wanted it over with.

Thomas Garvey finished milking the cow and wandered back to

his friend. After a while Ellen left, and came back, and then left and came

back again. The two men watched from under the apple tree.

“She’s doin’ fine. Mrs Brien says she’s doin’ fine. Still a

while though,” Ellen said as she passed the second time. Edward and Thomas silently

watched her go back into the house.

“Time for an ale. What about ye?” Thomas Garvey said

finally.

“You go. I’ll wait. Thanks for comin’”.

Thomas Garvey’s loyalty to his friend at last succumbed to

his loyalty to a good ale and he made his way to the Castledrum alehouse, where

he knew the publican, Patrick O’Flaherty, would welcome him as a long-lost

friend, since all of yesterday.

Back in Ardcanaght Mary’s labour ended soon after as she

delivered a baby boy, which they named Edward.

Frances Brien gave strict instructions. “You must protect

the child from the fairy changelings. Wrap the newborn in his father’s

trousers, and when you place it in the cradle you must put it in a horse’s

harness. Hang the fire tongs over the cradle – fairies are frightened off by

fire. You must make the sign of the cross over the unbaptised baby every time

you pick it up, and anyone who picks it up must do the same and say “God Bless

you”. And remember – you must be cleansed before you can return to the parish. Four

to six weeks. Maybe Father O’Sullivan will allow you to go to the baptism, but

you must be churched before you can go back to normal. I will return tomorrow.”[ix]

On 4 May 1816 Mary and Thomas proudly held their newborn as

Father O’Sullivan baptised Edmundum Griffin (baptismal entries were always

entered in Latin). Ellen Mahony and Thomas Garvey sponsored the child. Father

O’Sullivan promptly doused young Edmundum Griffin with holy water before the proud

parents wrapped him up against the fickle May winds and retired home with friends

to celebrate another of God’s souls being signed up for the good fight.

[i] https://www.yourirish.com/traditions/may-day-customs

[ii] https://irishorigins.wordpress.com/2016/04/30/irish-customs-may-eve/

[iii] https://www.yourirish.com/traditions/may-day-customs

[iv] https://www.yourirish.com/traditions/may-day-customs

[v] https://thefadingyear.wordpress.com/2020/04/30/may-eve-the-fairies-in-irish-folklore/

[vi] https://perceptionsofpregnancy.com/2016/02/15/always-ready-handywomen-and-childbirth-in-irish-history/

[vii] https://thefadingyear.wordpress.com/2020/04/30/may-eve-the-fairies-in-irish-folklore/

[viii]

https://www.academia.edu/19692606/Women_Childbirth_Customs_and_Authority_in_Ireland_1850_1930

[ix] https://www.academia.edu/19692606/Women_Childbirth_Customs_and_Authority_in_Ireland_1850_1930

Comments

Post a Comment