All at Sea - Part 2

Illustrated London News - July 29 1848

We went down into the hold, which was fitted up with berths, if such a name may be given to the tiers of un-planed deal boards, which resembled large hen-coops piled one above another; and stretched on mattresses upon these wooden gridirons we saw many of the emigrants, waiting wearily for the appointed hour that was fixed for sailing. It made the heart sicken to picture that hold, when out at sea with the hatches battened down, and the vessel driving through a storm. There were little children running about, and playing at hide and seek amongst the bales and casks – fair-haired, red-cheeked, blue-eyed beauties, whose sunburned arms and necks told that they had had the run of the open village green; and such we found had been the case when we enquired. Both father and mother were fine specimens of our English peasantry; the grandfather and grandmother were also there. ...

A wretched-looking Irish family occupied another corner. All seemed to regard this miserable group with an eye of suspicion more than of pity, for it was whispered that a few biscuits and a little oatmeal was all the provision they had made for the voyage. The captain, however, who had had some experience, considered that they were amply provided, and he had made the strictest inquiry of them. A bag of coarse bread, which had been cut into slices and then browned in the oven, had that morning, he said, been sent on board to assist them - it was the gift of a few poor Irish people who lived in the borough of Southwark. This bread, he said, with a little suet, made excellent puddings; and he promised that they should not lack the latter ingredient. As he said, “We never yet allowed one to starve; but this is a queer lot.”

https://www.theshipslist.com/ILN.shtml#emig1848

"Five more?!" The Surgeon-superintendent was sitting at dinner in the officers' quarters, hearing Matron Chivers' daily report. She had been following the progress of the Quin girl closely, but was happy for the handywomen to take care of the pregnancy for the time being. The good doctor knew she must be due soon, and then he'll step in if necessary, but hoped he wouldn't be required. But now Matron had news which would surely involve him.

"Five?" he repeated.

Matron had formed a closer relationship with some of the Irish handywomen, and they were able to confirm that another five passengers had babies on the way which would be delivered well before the ship reached its destination. "Probably all in December, God willing" Matron informed him casually between sips of her beef soup.

"I'll set up a surgery in my quarters. Tomorrow morning I want to see all of them personally. How's the Barnes girl?"

"Still coughing her heart out, poor thing. She struggles to make her way up the stairs to the poop deck to get the fresh air. I don't hold out much hope. She has a brother Richard who comforts her, and the two Ahern girls - Catherine and Margaret I think - are very close. All from Cork."

The Surgeon-superintendent had been doing his homework and had found an oration on pulmonary consumption by Charles Wilder from the Massachusetts Medical Society ("Quite recent too - 1843" the doctor noted).

"The Cork girl fits a number of the eight dispositions for phthisis - that's what they call it. Damp soil or air, probably insufficient food, clothing and exercise (or air, or light), quite possibly hereditary, not to mention depressing passions. There's a lot of phthisis in Ireland now."

"Nothing we can do then?" Matron asked.

"No. We'll have to let God's will take its course. Wilder says pure air, clean lodgings, temperature taken daily, and some exercise, but she's third stage so all we can do is provide the poop deck if the weather's fine and she can climb. She'll be in a lot of pain which I'll have to address with opium eventually, but that's in short supply. Let's hope it doesn't spread."

The following morning the Surgeon-superintendent received the five hopeful mothers-to-be and confirmed that they were healthy as far as he could determine. Then he returned to his medicine cupboard again to check his supplies. He had some time on his side - it appeared that all the women were over 30 weeks, so in a few weeks he was in for a very busy time indeed.

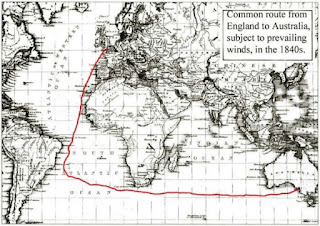

Day 52 Nov 11 1854 Lat. 32° 20”S Long. 15°24"E Saturday - The Captain was concerned. To this point the weather for the voyage had been predictable - it was hot and steamy across the tropics, with occasional days of no wind at all, and it had steadily got cooler as they headed south. Last night was the first time they had encountered a storm, however, and the ship was not handling it well. He had ordered a double reef to be taken in the main and fore-topsails, as well as the fore-topmast stay sail. The storm soon abated, and in the morning the drenched sailors and passengers emerged to begin the process of drying out their bedding and belongings. Through the night the groaning and creaking from the old ship was only matched by the terrified screaming from the Irish girls in the poop - they were sure they were about to meet their maker, and numerous decades of the Rosary were muttered between the screams.

The storm had passed but the wind kept up, and the ship, like the barnacled whale she resembled, heaved and wallowed as the rising sea commanded. The Captain decided that the sails should be raised again, and the crew, cursing and drenched, scrambled to the masts. The emigrants who remained above deck were rewarded for their bravery by being swamped by the wash, forcing the Captain to order all down below once more. This was much easier ordered than obeyed, as the lurching ship sent them tumbling in all directions as they tried to make the hatch.

By his reckoning the Coromandel was only a few days from the Cape, but unless there was an emergency they would continue past this last vestige of humanity and civilization and on into the Great Southern Ocean, where if all goes well the Roaring Forties will carry them quickly onwards to South Australia. Unless, that is, they encounter another storm. Captain Byron had weathered many a storm at sea, but the stories he had heard of the storms in the Southern Ocean both chilled and energised him. Raging winds, seas like mountains one second, and canyons the next - he knew the old Coromandel would be lucky to survive if it was caught up in such a maelstrom.

RULES FOR PASSENGERS

MEALS & BED-TIME.

FIRES & LIGHTS.

CLEANING BERTHS etc.

VENTILATION.

MISCELLANEOUS.

BY ORDER OF THE MASTER.

https://www.theshipslist.com/accounts/rules1849.shtml

Day 71 Latitude 43º20”S56º51”E Dec 3 1854 Sunday - Captain Byron is a cautious man, but the signs so far as they scuttle swiftly across the Great Southern Ocean are good.

Since the good ship Coromandel entered the Roaring Forties the wind has been astern and this has enabled her to make about 200 miles per day. The emigrants attending the service this morning (the English ones anyway - the Irish keep mumbling their rosaries to themselves below deck) were occasionally dashed with spray which overran the bulwarks, but all in all the mood of both passengers and crew has been good.

It blew so hard last night that the Captain ordered the topsails to be close reefed. The wind blew a gale from the west-south-west, and the rolling of the ship led to dangerous conditions on deck. By morning the sun appeared wanly through the clouds and rain squalls. The Captain checked his chronometer and sextant at midday as usual and determined that they were on course, and should be arriving at Port Adelaide in about five weeks.

Below deck the emigrants occupied themselves with singing and dancing when the rolling of the ship allowed it. They all had their daily duties to perform before breakfast, which got everyone out of their bunks. The Captain received a report from Surgeon-superintendent Barlas that the Karl girl delivered a baby this morning, but the mother was feeling poorly due to debility. The mother was being attended by numerous Irish handywomen who told the surgeon that the birth was a difficult one - lots of screaming and shouting, the whole ship could hear it despite the gale blowing. The surgeon indicated he would monitor the mother's health daily. No problem finding wet nurses though - there's at least another four babies to be delivered in the next three weeks.

The Captain recorded the birth in the ship's log. "Karl, Sarah. December 3rd 1854, female."

Catherine Griffin's Diary

May God have mercy on our souls! So matron tells us this mornin that were goin on to Adelaide an no need to call into cape town so from now on we all alone cept for the almighy. Yesterday we got up on deck while the weather was fine an all we could see was water water water in every direction at least its cooler than the bakin oven we lived in before. God it was hot.

The girls whos babies are due are all ok - matron has told us unless theres problems shell leave it to the handywomen to manage an god knows ther are plenty of them. Seems every irish woman whos had kids is an expert i keep right out of it but Mary Murphy shes doin a good job of sortin out the sheep from the goats. Anyway young Bridie quins due any day now - she was throwin up from the minute she bunked down. Theres not enough water so matron has arranged for a bucket to collect rain water an dew an every mornin bridie gets a bucketful of fresh water to drink - same with the other girls. The men keep right out of it jus playin cards an singin songs when the moods up an the ships not tossin us all about.

Our Marys a character makes lots of friends with the other girls an boys her age. Every mornin the schoolmaster takes the kids off for instructin while we clean the cabins an bunks. Edward has got sweepin duties which he says is ok gives him a chance to wander about an have a natter with all an sundry - seems hed talk to a wall if it looked at him nicely. Lookin forward to a cuddle once this nightmare is all over. Some of the men have found givin up the grog to be a bit of a challenge, specily when they hear of the sailors gettin ther daily grog allowance. Do em good i think.

Our Thomas jus follows his Da around. Hes a Griffin for sure - doesnt matter who they are ther good for a chat - the sailors think hell be one of them one day he tells them if the sails need trimmin and if the ropes arnt tight enough. The school master told me he had to stop him from tryin to climb the riggins god help us whats he gonna be like when hes off the boat? He keeps a close eye on his sister Ellen when shes hidin between the bales an casks playin games with the others.

I'm six months now. Baby is doing a lot of kicking an rollin about. Even Edward is startin to get interested.

Day 81 Latitude 39º47”S Longitude 105º23”E December 13th 1854 Wednesday - the weather has continued to be fortuitous. The Roaring Forties has carried them like faeries and goblins up and over the waves - God has been kind to them. Below decks, among the increasingly cheerful and hopeful emigrants the spirits of renewal have been hard at work. Three more births, and the surgeon has had little need to interfere in any of them. Charlotte Breakwell - good English stock, married, family, from Surrey - delivered a baby girl on the 9th with little fuss. And yesterday Elizabeth Hammond - dad, Charles, is a blacksmith from Middlesex - brought another baby girl into the world. Both Charlotte and Elizabeth appear to recovering well, according to Matron's report to the surgeon. Then last night - another one! Bridget Kennedy, Irish lass from County Clare. Married to Patrick. The Irish handywomen took that one over - they'd been fussing over her for months anyway. Fortunately it seems all went smoothly, no doubt due to numerous Hail Marys, Glory Bes and Our Fathers which emanated from below decks and made their way like smoke rising to the heavens above. Baby boy it was.

Prayers, however, may not be enough for poor Sarah Karl. The surgeon thinks it may be puerpal fever. He reports to the Captain that the patient suffered blood loss during the birth, and then a few days later started to shiver and sweat, saying she felt hot. Then she would feel very cold, but have a high temperature, and say she was thirsty. Abdominal pain followed, and very high pulse. The handywomen say she has been vomiting, with lots of diarrhoea. Husband Robert has been by her side the whole time. He comes from good Lincolnshire stock. Their other children - Jonathan, 7, John, 4, and Elizabeth, who is 2, have been taken in by the other women, but it looks like they may be starting off their new life in a new land bereft of their mother. The decades of the Rosary have been continuing through the night.

There is one more birth to come in the next few weeks - Caroline Durrant. Caroline and husband Jonathan are from London. They have two children already - Jonathan, 7, and Sarah, 3. Matron reports that the pregnancy has been uneventful to this point.

All about below decks the emigrants are living closely with life and death. And the condition of "that poor girl" Mary Barnes continues to decline. Tuberculosis is slowly strangling the life out of the 21 year old. She is now too weak to climb the stairs to get up to the poop deck for fresh air, and for some weeks she has been lying in her bunk struggling for breath. The surgeon feels all that could be done has been done, and doesn't expect her to last much longer. "She's terrified of being buried at sea," explains Mary Murphy, who befriended the servant girl from Cork early on in the voyage. When the two infants were consigned to the depths of the sea on that terrible day a few weeks ago all the emigrants, including Mary Barnes, were above decks to watch. Prayers were said, and the two tiny bundles slid silently into the open arms of the ocean. Mary Murphy was watching Mary Barnes. "You shoulda seen the look in her eyes", she told Catherine that night.

For Edward and Catherine Griffin, and Mary, Thomas and Ellen, the future is there to be had, but fate can be kind as well as cruel. Life is fragile, and their faith provides them with the structure, routine, companionship, and inspiration necessary to hold them up. There are no priests aboard the Coromandel, so the Irish Catholic emigrants had to organise their own spiritual guidance through prayer and especially the Rosary. This caused some irritation to the Anglicans and Nonconformists, who complained to the Matron about the incessant Hail Marys, but wisely she avoided taking sides. "Be patient. In Adelaide there will be far more of you than them!"

Day 95 Latitude 35º21”S Longitude 125º11”E December 27 1854 Wednesday - Matron Chivers was 50 years old, from Surrey, and formerly a domestic servant. Although she knew her place, and most definitely the place of others, she was well-respected by the emigrants. "You can smell it, almost. She's a good woman, an if you tell her somethin she listens." Mary Murphy was nattering away, as she often did, while Catherine Griffin checked Ellen's hair for nits once more, with the fine bone comb she hid away when they boarded. Mind you, there wasn't much to check since the Matron had upset them all by telling them all the hair had to cut off to get rid of the nits problem all those weeks before. Ellen's scalp was itchy red from scratching away the flea bites she got from the woolen cap she had to wear afterwards, so Catherine was taking extra care.

But today Matron is feeling the weight of the responsibilities of her job. When the Emigration Agent approached her to say they needed someone to look after a few girls on a voyage to Australia, she was at first doubtful. But she was keen to emigrate - work opportunities for 50 year old domestic servants were scarce in Surrey, and since her husband died she had no family. Australia seemed exotic, and the stories in the London Illustrated News about the fortunes to be made in the Gold Rushes convinced her to take it on.

Then, a few days before the voyage she was finally shown the passenger list. She was shocked to discover "a few girls" was really 105 single women, mostly from poor Irish workhouses. And she had the general care of the other 180 as well! Being direct and honest by nature, the new Matron Chivers went directly to Captain Byron, but she soon discovered her complaints of having been misled were useless. "That's a sailor's life, to be misled," Surgeon-superintendent Barlas said dryly. "You're one among many. But if we stick together we'll get through it."

She took his advice, sensing the doctor was also a competent and compassionate man, and together they managed the daily crises as best they could. No one questioned the authority of the Captain, and fortunately the mainly favourable weather meant that an air of hopeful optimism settled over the good ship Coromandel on this voyage.

On the 23rd Caroline Durrant delivered a baby girl. The family Durrant from Paddington had now grown to five, and the surgeon reported that mother was doing well after a brief if tempestuous delivery, in the middle of a stormy night no less. "Ah, shut up woman, will ya!" one of the men shouted grumpily from the emigrants' quarters as the drama reached its climax. Since the beginning of the voyage all the men slept on the starboard side of the ship, while all the women and children slept on the port side, and women delivering babies were shepherded into a sectioned off area at the stern, hidden behind barrels and cargo boxes. Childbirth was strictly women's business, apart from the good doctor, but he mostly left it to the numerous handywomen who almost fought each other to get intimately involved. Afterwards there was much discussion, heated at times, about the advice given, and how practices differed in Clare or Wicklow or Cork.

Christmas came and went with little celebration. Two passengers were in a grave condition. Poor Sarah Karl was in agony. Her puerpal fever since giving birth over three weeks ago had continued, and the screaming and groaning from the associated abdominal pain was relentless. The Surgeon felt helpless. "It's a disorder of the blood's composition" he whispered to Matron Chivers. "I don't have anything to give her." The Matron shared the Surgeon's helplessness. "Maybe more water?" she asked. "Not unless it rains. We're running short on water. The sooner we get to Adelaide the better."

But if Sarah Karl was in a bad way, the situation with Mary Barnes was about to be resolved. "It's horrible watching someone die from phthisis," Barlas said. "You're slowly drowning in your own fluid." Mary's breathing was very shallow, and was more of a rattle than a breath. Her face was bloodless, and her hands and feet were slowly going black. The Irish women were allowed to go to the single women's quarters at the rear of the ship where, among the heat and smoke from the galley next door, they recited the Rosary in shifts in the corner set aside for Mary Barnes. There was a small porthole, no bigger than a Bible, through which Mary Barnes could get some fresh air, but the end came on December 26th, when the rattle stopped.

Matron Chivers had just finished entering her daily report when she thought she could hear high-pitched wailing coming from the emigrants quarters, but discovered it was really coming from the rear of the ship. All the single girls were huddling together, silent, as the older women let out their wailin' and keenin'. "May God have mercy on her soul" Mary Murphy said to the Matron as she entered the smoky dim hellhole the girls had been occupying all this time. She rushed to find the Surgeon to certify the death. Within a few hours Mary Barnes, 21, servant girl, emigrant hopeful, was wrapped in cloth, pinned through the nose, and disposed of with whatever humanity could be roused at that moment, to the bottom of the Great Southern Ocean.

| The South Australian Government Gazette 1866 p. 88 | ||||

| Name | Age | Date of Death | Cause of Death | Where buried |

| Donnell, Catherine | 1 | November 6th, 1854 | Diarrhoea | at sea |

| Fox, William | 5mo. | November 6th, 1854 | Thrush & pneumonia | at sea |

| Barnes, Mary J. | 21 | December 26th, 1854 | Pulmonary consumption | at sea |

| Kurl / Karl, Sarah | 39 | January 12th, 1855 | Debility & gangrene | on shore |

| Surgeon Superintendent Report | ||||

| Name of Mother | Date of Birth | Sex of Infant | ||

| Quin, Bridget | November 16th, 1854 | female | ||

| Karl, Sarah | December 3rd, 1854 | female | ||

| Breakwell, Charlotte | December 9th, 1854 | female | ||

| Kennedy, Bridget | December 12th, 1854 | male | ||

| Hammond, Elizabeth | December 12th, 1854 | female | ||

| Durrant, Caroline | December 23rd, 1854 | female | ||

http://www.theshipslist.com/ships/australia/coromandel1855.shtml

Day 105 Latitude 39º29”S Longitude 134º50”E January 4 1855 Thursday - Edward Griffin was above deck tending to his beloved chickens. There were originally 40 of them when he was given the job by the ship's cook soon after the Coromandel left Southampton all those weeks ago. Now there were only half that number. Most had died due to exposure or cold, and whenever he found another poor frozen chook in the morning Edward was quick to inform the cook that he could add another one to the pot for a quick warming chicken broth.

All the emigrants were expected to muster on deck at 10 am, weather permitting, to hear the Captain mutter a few prayers and Matron or the Surgeon-superintendent address any issues. On this day there was only good news. "We should be expecting to sight land within a day or two, and a few days after that to be disembarking in Adelaide. Make sure all your papers are in order, and that you have secured all your belongings."

A great cheer arose amongst all who heard this news. After the misery of the voyage, the air was full of cheery chatter. They moved back downstairs to their quarters with renewed energy and purpose.

"There ya go, my little ones - we made it." Edward's mutterings to his chickens had not gone unnoticed by Glint-in-his-eye. The two men often had a natter if Tommy Shepherd (his real name) happened to be rostered on deck after the daily muster.

"They'll never talk back to ya, ya know."

"They know what I'm sayin'," Edward replied. "What'll you do once we get to Adelaide?"

"Get drunk." Tommy's directness was typical. "Mind you, I hear Adelaide's full of churchy types - Methodists an Presbyterians an those German Lutherans. Doesn't sound much like a lot of fun to me. Be glad to get out of the place. Why would you want to spend the rest of your life there?"

The last question was directed at Edward. Of course, this was something he had plenty of time to think about once the safety lamps were extinguished every night. Why indeed? Why cut yourself off completely from everything you've known, everyone you've known, every place you've loved, from Dingle Bay to Milltown market to the pub in Booleens to the games of caid in Kilgarrylander parish - for a life on the other side of the world?

The answer, he'd decided, was simple. There was no choice, and Adelaide meant an opportunity when there were no opportunities anymore in Ireland.

"It's somethin'. Before there was nothin'. An I'm sure there'll be a pub in Adelaide somewhere. Maybe I'll see ya there."

"I'll be sailin' out once she's ready," said Tommy. "I wish you well."

The next afternoon Captain Byron checked his sextant and chronometer again. He concluded that if all went well the Coromandel should be in sight of landfall in a few hours. They were within reach of Kangaroo Island. Before nightfall the crew reported the coastline to the east and a little later to the north as well. Even though it was a good twenty miles of open water between Kangaroo Island and the Althorpe Islands he decided he wanted to do the passage into Gulf St Vincent in the daylight, so he ordered the sails trimmed so the ship made little movement through the night. The balmy January weather was on their side again.

Day 108 Latitude 34º46”S Longitude138º33”E January 8 1855 Monday - yesterday morning the passengers aboard the Coromandel woke to a glorious sight - land to their left and right, so close they felt they could reach out and touch it. In reality it was ten miles or so from them either side but that didn't matter. The 10 am muster looked and felt like a religious revival - the prayers and responses were much more earnest, and the sense of relief was so strong it almost blew the ship along by itself.

Since then all aboard were in a fever of preparation and excitement. God had been with them all along. They spent what they thought would be their last night aboard the Coromandel unable to sleep. There was a great deal of merriment below decks well into the early hours. Their futures were within easy reach.

On their final day the weather had been generally fine, even though the coast of Kangaroo Island and the land beyond Backstairs Passage to their south occasionally disappeared in fine rainy mist. And there were other ships! People! People doing normal things like sailing up and down from here to there along the coast. Soon enough the mailman appeared to collect the letters to distribute to Adelaideans lucky enough to get one. He wasn't wearing any shoes or stockings, and seemed very.. well, colonial in appearance to some of the emigrants.

Then the Pilot came aboard and after a brief chat with the Captain hopped off again. A steam tug was ordered and the Coromandel made its way under tow into a wide river with swampy edges where it was difficult to see any land in amongst the mangroves. Edward and Catherine joined the other emigrants peering into the distance to see a low range of hills in the distance. It was hot. The heat seemed to rise up off the land in waves. This clearly wasn't Dingle Bay.

Then a cry went up as they saw a pig feeding on the water's edge, and a ramshackle hut behind it, then a person on the shore waved and all the emigrants waved and shouted back. Then the river opened up a little to reveal other ships at anchor, and a fine looking building which Tommy said was the Customs House. At first it appeared to stand alone, tall and square against the flat plain, with the low hills brooding and uncaring in the background. It could have been transplanted from Southampton docks, and flaunted its importance to the settlers and immigrants, if no-one and nothing else. Then other buildings appeared, and the semblance of a port town took shape. People - people! - stood on the dock, and horses carted goods here and there. Further across the water small boats ferried passengers between ships. The Captain shouted something, and the tow was released, and the good ship Coromandel weighed anchor.

They had made it.

George French Angas, Port Adelaide, 1846.

https://res.cloudinary.com/odysseytraveller/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto,dpr_auto,w_765,h_536,c_limit/https://cdn.odysseytraveller.com/app/uploads/2020/05/Port-Adelaide-1846.jpg